One year ago, with the blessing of Donald Trump, Turkish forces invaded Rojava seeking to perpetrate ethnic cleansing in order to forcibly resettle the area, committing summary executions and displacing hundreds of thousands of people. Since 2012, the autonomous region of Rojava had hosted a multi-ethnic experiment in self-determination and women’s autonomy while fighting the Islamic State (ISIS). Anarchists participated in resisting the Turkish invasion, some as combat medics on the ground in Syria and others as part of an international solidarity campaign. To this day, Turkish forces continue to occupy a swath of territory in Syria, but they were blocked from conquering the entire region.

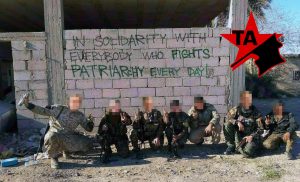

Anarchists from around the world have been involved in the experiment in Rojava for many years, joining the YPJ and YPG (“People’s Protection Units”) at the time of the defense of Kobanê against the Islamic State and later forming their own organizations, including the International Revolutionary People’s Guerrilla Forces (IRPGF) and most recently, Tekoşîna Anarşîst (“Anarchist Struggle,” or TA), founded in autumn 2017. In the following extensive interview, several participants in TA compare their experiences fighting the Islamic State and fighting Turkey, explore what has occurred in Syria since the invasion, evaluate the effectiveness of anarchist interventions in Rojava, and discuss what others around the world can learn from struggles in the region. This is an important historical document drawing on several years of experience and reflection. For anarchists who oppose all forms of hierarchy and centralized coercive force, the establishment of armed self-defense organizations poses many thorny questions. While the following interview does not conclusively answer them, it will inform any discussion of these issues.

For more background on the Turkish invasion of Rojava, read “The Threat to Rojava” and “Why the Turkish Invasion Matters; for background on the agenda of the Turkish government in the region, read “The Roots of Turkish Fascism,” authored by Turkish anarchists.

A glossary of acronyms and Kurdish terms employed in this interview appears as an appendix.

—What has occurred since Turkey attacked Rojava in October 2019?

Garzan: We discussed the humanitarian crisis that followed the Turkish occupation in our last interview. Since that invasion, Rojava has seen the longest period without active front-line fighting that we have experienced. There are still operations against ISIS sleeper cells in Deir Ezzor and occasional Turkish army attacks on the front lines at Ain Issa, Manbij, and Til Temir, but the SDF [“Syrian Democratic Forces,” the umbrella structure for military forces fighting to defend the Autonomous Self-Administration of North East Syria] is taking this time to prepare for the next major Turkish attack. The military academies are training new forces; the cities close to the front lines are preparing their defense systems, digging tunnels and creating other infrastructure for self-defense. The diplomatic bodies of the self-administration are working to reach agreements with different forces inside and outside Syria, pushing for political solutions, because this revolution is looking for peace, but knows that we have to be ready for war.

Mazlum: The military incursion of Turkey and its proxies into NE Syria is an ongoing process that continues to this day. The attack on this region includes all the bombs and rockets dropped on people’s houses, all the crops burned, all of the people who have been killed including our comrades and countless children, every bullet shot on this land, every home lost, all the people who are now refugees in their own country. But all that is only part of what is happening. The Turkish state is also carrying out specialized warfare in the fields of information and propaganda, intelligence and espionage—curtailing the freedom of women, blocking access to water and other essential resources, erasing culture, sabotaging the economy, and undermining ecology. It is playing war diplomacy on a massive scale. For instance, after capturing Serêkaniye, in 2020, Turkey turned the city’s SDF cemetery—where people killed fighting Daesh [the Islamic State] are buried—into a military base for the jihadist factions of the SNA. This illustrates how this warfare is carried out.

Imagine an intense front-line battle. Then imagine the equivalent of that taking place on an everyday basis in every sphere except physical fighting with weapons. That is what has been happening since the beginning of the invasion in 2018 in Afrin, and now after the seizure of Serêkaniye in 2019. The invasion has never stopped. It is a low-intensity war in which the tension is constant but clashes rarely occur. The chief moves take place on a different level, setting the geopolitical conditions in the region and preparing the way for the next military offensive.

Botan: There have also been issues with Daesh prisoners—prison riots and prison breaks. The self-administration is getting little or no support for processing these captured Daesh judicially, and is continuing to bear the strain of housing them while preparing for defense against further Turkish aggression. Turkey has also targeted revolutionaries in drone strikes on civilian areas—for example, the murder of three women of Kongra Star in Kobanê in June.

—How have the Turkish invasion and COVID-19 affected the lives of people in Rojava?

Garzan: We also discussed how COVID-19 affected NE Syria in our last interview. The first wave in March infected less than 50 people, thanks in part to the fast preventive response of the self-administration, and in part due to the embargo and blockade that makes it very difficult to travel in and out. Unfortunately, a second outbreak took place in September, starting from the Qamişlo airport, controlled by the Syrian State, and spread all around the main cities in northeast Syria. Right now, we have around 1800 detected cases and 70 deaths, but due to the lack of medical facilities that can conduct tests, it is possible that the numbers are higher. The self-administration was enacting preventive measures at the beginning, forbidding travel between cities and encouraging the use of masks. There was also a curfew for shops and other public places, except food stores and pharmacies, which were only allowed to open some hours in the morning. In general, people took the virus a bit more seriously in this second wave, but after years of war, it is difficult for the population to take an invisible threat seriously, and social distancing measures are difficult to follow in a society that is so heavily based in community, in sharing life together.

You can read a detailed discussion from two internationalist medical volunteers regarding how NE Syria is handling the coronavirus pandemic here in Russian. Updates on this subject are available from the Rojava Information Center.

—Describe the differences between fighting ISIS and fighting the Turkish military. What were the different challenges, tactically, politically, and also emotionally?

Garzan: The most obvious difference is the military technology that the enemy is using. ISIS was fighting with rifles and small artillery; they specialized in car bombs, suicide attacks, and well-made IEDs (improvised explosive devices). The Turkish state is fighting with proxy militias who have tanks and air support from drones and warplanes. Not many Turkish soldiers are on the front lines, however; on the ground, the enemy is the same as before. It has been widely documented how ISIS fighters put away the black flags of the Islamic State to fight under the red flag of the Turkish state, so now they have air support from an army involved in NATO. This forced us to change tactics—how we move, how we defend both military forces and civilians. The front lines are no longer the trenches where the YPJ/G formed, nor the deserts that the SDF liberated from ISIS. Now the front line is everywhere that Turkish planes and drones can fly.

Politically, it is also a big challenge. When we were fighting ISIS, everyone understood that it was a fight for all humanity, to stop a form of theocratic fascism that used brutal torture and executions as propaganda. But now that the Turkish state is continuing what ISIS couldn’t achieve, the challenges are much bigger. Not only are the military force and technology of the Turkish state much more advanced than those of the Islamic State, their political and media warfare is stronger, forcing the SDF and the self-administration to put a lot of effort into diplomatic relations with other powers to defend the liberated territory. Maintaining diplomatic relations also means crafting a narrative that other forces can support, because if the self-administration talks openly about a revolutionary horizon of democratic confederalism—that is, overcoming nation-states and bringing down capitalism and patriarchy—it will be easy for Erdoğan to get a green light from the superpowers to wipe out this liberated territory.

Şahîn: There is an elevated risk for internationals, particularly those who fight with weapons on the front line. Several states that did not go after “their citizens” for coming here to fight ISIS have changed their policies or stopped looking the other way and are now pursuing people who return much harder. And not only fighters. This should not affect one’s decision to come, but it is important to understand the risks and position ourselves to minimize them while not decreasing our will to struggle.

Another difference, and for me this was a huge one, was emotional. The last years against Daesh, we were on the offensive—the liberating side. However dangerous the enemy was, there were ways to do battle. Fighting Turkey, we were on the defending side, in a situation in which sometimes the front line was behind us and we could not be sure how things would turn out. It is important to believe that there will be ways forward again, that we will defend this land and liberate what was lost; yet in the midst of this reality, this process takes its toll. It is one of the hardest mental tests one can go through. But if we cannot perceive the possibility of victory, we can never win. This means we need to have a strong belief and be smarter, in order to identify the Achilles’ heel of the enemy. It may be well hidden, but it would be a big mistake to say that just because they are stronger and bigger they must be unbeatable.

Mazlum: The emotional challenge that stands out to me is having to apply military discipline in situations in which the lives of people were directly at stake and we could help them, yet by the order of the command line we couldn’t do what we considered necessary according to our own judgment. There were many situations like this. For example, once, we learned that several comrades had been hit by a drone strike a few kilometers down the road. We knew that they were wounded but still alive. We also knew that a drone was circling around the area, waiting for people to come to help the wounded in order to strike again. For that reason, there was a strict order not to move anywhere—and we could understand such an order after seeing with our own eyes how other comrades were bombed and killed because they lacked discipline and moved at the time when they were told to not move under any circumstances. At the same time, we knew that our comrades were bleeding and that the difference between life and death is reckoned in seconds in such a case. In cold mathematics, we knew that the choice was between leaving several comrades to almost certain death and sending a combat medic team to rescue them that would likely be bombed and killed as well. In such moments, you can only imagine what is running through the minds of the wounded comrades and what you would feel and think if it were you lying burned and bleeding on the ground, realizing that you are being used as a trap. That is a specific psychological and tactical situation that we have had to deal with. This strategy is consciously used by the Turkish military, capitalizing on the psychological impact of airstrikes and drone surveillance and missiles.

SDF had already experienced this in 2016-2017 in clashes around Al-Bab, when Turkey used drone surveillance and air strikes. In the war against Daesh, we could see the positions of jihadists hit by air strikes. Now, we are the targets coldly observed by the trained operators of NATO’s second biggest army.

—How has the relationship between the self-administration and the United States changed over the past year? What appear to be the current priorities of the United States in the region?

Şahîn: One could encounter the US military on the front lines fighting Daesh—in field hospitals, artillery points, and air support. This does not happen on the front lines fighting Turkey.

Turkey started their offensive a few days after Trump announced US withdrawal from Syria. This was all staged; the USA would not leave the oil fields so easily—and they have not. In the months before the invasion, the US army positioned itself as a broker, making different deals with Turkey and SDF on the pretext of ensuring a “peaceful” solution. In the end, to the frustration of many, the SDF cooperated, taking down several defensive positions, withdrawing heavy weaponry 30 kilometers from the border, diminishing the number of staff at the border military points, and letting Turkish armed vehicles patrol with US vehicles within the liberated zone.

None of this mattered. Trump made his reckless decision. In the end, all these steps just weakened the defense and made it easier for Erdoğan and his jihadist proxies to invade.

Not everyone in NE Syria is a revolutionary. Some saw the USA as a positive force, given the fact that it helped to push Daesh away and was on the side of heval [“comrades” in Rojava], who present a true alternative to forces like Bashar Assad’s regime, ISIS, or TFSA [the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army—the jihadist groups backed by Turkey in the occupation of Northern Syria]. After this betrayal, everyone in the region understood the other edge of the sword of US politics. Throughout this society, feelings of distrust became quickly apparent.

The SDF understand that the civil war in Syria involves complex challenges. Consequently, they did not take the path of retaliation, but try to position themselves to advance the people’s defense as much as possible. On the field, this means that cooperation with the US army continues in some places, though the SDF fully understands that the USA would not turn their weapons against Turkey to defend NE Syria. These contradictions are hard to understand and SDF holds responsibilities to many different groups that are very difficult to fulfill.

Garzan: Regarding the priorities of the USA, we can quote Henry Kissinger: “America has no friends or enemies, only interests.” There are different agendas behind US policies, and sometimes they don’t even fit each other. The contradictions between the White House and the Pentagon had been visible on several occasions. When Trump stated that US troops would remain in Syria only to maintain control of oil reserves, moving away from the border positions where Turkey was about to invade, that was an indication of different priorities. On one side, the White House desired to please Erdoğan, who was getting too close to Russia and threatening the stability of NATO. On the other side, the Pentagon wanted to control the expansion of Iranian influence in the Shia crescent and curtail the advances that Shia militias made while fighting ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Eastern Syria has a number of oil and gas resources, and the US administration wanted to prevent Shia militias from gaining control over them and to keep Iran from establishing a full Shia corridor to the Mediterranean, connecting Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

On the ground, this looks like big armored vehicles with US flags on the roads, moving around and handing out candies to kids in random villages. They were sharing pictures of this on social networks, trying to move away from the images of one year ago when Kurdish people threw stones and tomatoes at their cars after the betrayal that led to the Turkish invasion. The coalition [i.e., SDF] has been carrying out operations against ISIS and supporting the raids of anti-terror forces against sleeper cells, but also carrying out operations in Turkish-controlled areas like the one that allegedly killed Abu Bakr Al-Bagdadi, leader of the Islamic State. This operation was publicized worldwide, sometimes also mentioning the intelligence support provided by the SDF.

Kurdish residents in the city of Qamishli express their anger as US military forces withdrew from Rojava to open the way for Turkey to invade.

—In retrospect, how do fighters in Rojava view the relations with the US government that led up to the Turkish invasion?

Mazlum: Just six months before the Turkish invasion, in October 2019, the SDF militarily defeated Daesh in the battle of Baghuz Fawqani after several years of fighting that was generally supported by the “international community.” Related to that, there was a certain assumption, or maybe rather a hope, that because of this, the international community would not permit an invasion that would lead to the slaughter of people in NE Syria. This was not something people clung to until the last moment, but it was a question everyone asked themselves. Now, we can look back and ask: what is international community? Do we understand that as all the people, institutions, and media outlets around the world that take an active international political stance and speak on the matter? Or is it the group of state leaders with their ministries and geopolitical interests? If latter, then we can’t expect anything different from the entities that sell weapons to Turkey today, condemn the war tomorrow, and the next day both reaffirm the importance of and support for the NATO alliance, while carrying out waves of repression against the Kurdish liberation movement in their own countries at the same time. A fundamental mistrust of the political establishment and states is something that anarchists share with lots of people in NE Syria. “There are no friends but the mountains” (Ji bilî çiya hevalên me tune ne), as the Kurdish saying goes.

And if we understand the “international community” to mean all the people, institutions, and media outlets around the world, we can agree that it is important for people to speak up about what is happening and spread the word. But honestly, if we are to hope for the international community to stop the invasion, it would have to not only protest against the invasion but rather fight against it and disrupt the Turkish war economy. Also, we can see that we ourselves as anarchists do not have a strong enough revolutionary movement to set an example that could be followed.

The question to us is then: how much can we rely on the vague term of “the international community,” when we need to defend and change our societies right now? And what is it that we can build and rely on, so we will not be alone when the bombs fall on our heads? Not only in terms of physically being alongside our comrades in these moments, but rather on the scale of sincerely feeling with our hearts that what we defend and fight for is connected to other people and places around the world?

—How has the relationship changed between the self-administration and Russia?

Garzan: Relations with Russia had been difficult since they handed over Afrin to the Turkish invasion in 2018. That was a big betrayal. It caused the self-administration to rely more on the US—until they did the same, handing over Serêkaniye and Gire Spi to Turkish occupation. After that, we can see how the self-administration took more initiative in diplomatic relations with the Russian Federation, seeking to cut out the regime in order to negotiate with the ones who really make the decisions in Syria. It is important to bear in mind the great number of Kurdish people who live in Russia—much more than live in the US—which helps when it comes to diplomacy.

Their policy seems to always find a balance between the relations with US and Russia. For example, Ilham Ahmed, representative of the Syrian Democratic Council, visited Moscow some months after a conference at the White House. After the agreement regarding the oil fields in Deir Ezzor with the obscure American company Delta Crescent, negotiations about the gas fields opened with Gazprom, the main energy company linked to the Russian state. Russia is a very pragmatic state regarding diplomacy—but Russia focuses more on Turkey, not only in negotiations regarding weapon sales and other economic interests, but also in order to move them away from NATO and weaken the supremacy of the US.

—What are the power dynamics now between Assad’s government and the self-administration ?

Şahîn: The SAA [Syrian Arab Army, the military force of the Syrian State] is present on some of the front lines with Turkey, though this is more a matter of diplomacy from their side. There is a common enemy but very different aims. Consequently, they have much less will to fight Turkey and a different relationship to allies.

The conflict with the Assad regime is more political and economic. Heval don’t waste energy and resources contesting SAA and it would not be the best choice. Negotiations failed because the two opposing positions were too different and too intractable to find a common path. Assad is trying to undermine the revolution by offering better prices to farmers, cutting the electricity, and similar tactics. He has no support among the Kurdish population in NE Syria, but among the Arabic and Assyrian populations it is more complex. He tries to play the game of divide and conquer. Heval know that. It is already one of the objectives of the revolution—democratic confederalism—not to base the new society on a singular national or ethnic identity, but to find ways that diverse communities can live together, perhaps with semi-autonomous areas on the same land. This is one of the key points of the stateless solution based on Öcalan’s proposal.

Garzan: Assad’s government is based on the logic of the nation-state. It survived the war due to the external influence of Russia but also the internal influence of hard nationalist factions, like the national socialist party of Syria. This makes it impossible for them to accept the proposal of the democratic nation and the confederal model proposed by the self-administration. When negotiations are not advancing, the regime comes back to the strategies that all states employ to ensure their hegemony—violence and repression. In summer 2019, a wave of fires destroyed crop fields in NE Syria. Wheat is one of the main resources of NE Syria, so that was a hard blow for the economy of the self-administration. At the beginning, people suspected that Daesh was behind it, but most of the people arrested lighting the fires turned out to be members of the intelligence services of the Assad regime. In November, as a consequence of the Turkish invasion, the common threat to Syrian territorial integrity gave rise to negotiations that resulted in an agreement of common deployment around the Turkish border. Both military forces are on the front lines to fight the TFSA, but political negotiations did not progress. Now Russia is starting a mediation process, publicly supporting some of the demands of the self-administration including some degree of autonomy, political representation in the constitution committee and the Geneva peace talks, and making Syria a federal state. The regime is not very happy about this, but their dependency on Russian support makes it difficult for them to oppose Russia’s decisions.

—Looking back on the first phase of the Syrian revolution from this vantage point in time, were there any missed opportunities early in the process?

Garzan: It is very interesting to reflect on the first years of the revolution, the so-called Arab Spring, in order to analyze how events followed each other to bring us to where we are today. In those times, almost ten years ago, a lot of different forces opposed the hegemony of Assad’s regime. In short, we can say that the first wave of democratic uprisings collapsed when the situation escalated to an armed conflict, but the story is more complicated than that. This wave of democratic uprisings was diverse and organic, like the local councils organized in different cities with a revolutionary perspective. A network of local councils emerged, influenced by the life and work of Omar Aziz, a Syrian anarchist who took active part in the uprisings until he was arrested and died in the prisons of Damascus. These uprisings received support from Western societies, and the regime knew how dangerous a movement can be when it gains the support of Western public opinion.

In the military side, the creation of the FSA (Free Syrian Army) in opposition to the SAA (Syrian Arab Army) marked the beginning of the civil war. The Assad regime endeavored to crush the revolutionary forces and enable other currents to gain control of the popular uprisings, opening the door to Salafist and other Islamist groups to take over. They released Islamic fundamentalists from the jails in order to make space for the activists organizing the uprisings. The military escalation damaged the democratic, socialist, and secular movements, while the Salafist groups were more used to operating in clandestinity as an insurgent force. When Daesh began to penetrate into Syria in 2013, several Islamist factions defected from the FSA and joined ISIS. When al-Baghdadi declared the caliphate in Mosul in 2014 and their forces moved into Syria from Iraq, they started to advance at the back lines of the FSA. With the regime on one side and ISIS on the other, the territories under the control of the opposition were crushed under the flags of the caliphate.

In Rojava, the situation was different. The Kurdish movement’s experience of long-term resistance, especially in the past thirty years of war against the Turkish state, equipped them to navigate the convulsive waves of events. At the beginning, the Kurdish movement managed to push out the representatives of Assad’s regime with minimal use of force, simply by outnumbering the regime soldiers and forcing them to leave. Kurds took the opportunity to start a revolution during those convulsive times, but they kept their distance from the Arab opposition due to mistrust and caution. We should not forget about the oppression that Kurds have experienced as an ethnic minority, with their language not recognized, their nationality questioned, their likelihood of ending up in jail or living in poverty much higher than for those of the majority ethnicity.

And of course, there were also divisions within the Kurdish population. Armed Kurdish militias were divided between the YPJ/G loyal to the PYD [a political party committed to the ideas of democratic confederalism], militias linked to the PDK-Syria [a political party connected with PDK of Iraq, the most influential Party in the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq], and other militias without clear affiliations. Kurdish militias were involved in some clashes against the regime, but the first major clashes took place when the YPJ/G started to fight against Islamist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al-Qaida. As the fights escalated and the war intensified, weaker factions were absorbed by stronger factions or just disbanded. When ISIS started to penetrate into Syria in 2013, the opposition factions had to chose sides—with Daesh or against them. At this time, a coordination began between the YPJ/G and other revolutionary opposition groups under the name Euphrates Volcano. ISIS gained ground and strength, starting the siege of Kobanê, where it was ultimately defeated. The SDF formed and started the offensive against the caliphate. This video offers a full overview of how territory shifted during the conflict.

It is difficult to pinpoint what could have gone differently. We can imagine different scenarios, but they would be purely subjective speculation.

The first idea that comes to mind is that if Bashar al-Assad had negotiated with the opposition during the first months of the uprising, we can imagine a transitional process in which some reforms would have begun in the Syrian state, some concessions would be made to the opposition, and parts of the opposition would be integrated in the state according to a strategy of divide and conquer. This would have isolated the movements pushing for a radical transformation—on one side, the Kurdish revolutionary movement, and on the other, the Salafist groups like al-Nusra. In this scenario, we can imagine a Kurdish political opposition trying to bring their demands to the transitional government; in all likelihood, their demands would have been dismissed. Any attempt at a revolutionary movement in the Kurdish areas would have been crushed by the Syrian Arab Army, which would not have been busy defending the big cities in this scenario. This scenario doesn’t suggest any opportunities to bring to a better revolutionary situation.

A second scenario might have involved a more organic coordination between the revolutionary opposition and the Kurdish movement, in which a wider revolution would bring down the Regime before they could consolidate support from Russia. I think this was the scenario that Bashar al-Assad feared the most, and that’s why he put so much effort into crushing the opposition, bombing the protest mobilizations, and releasing Islamists from prison to ensure that the opposition would be controlled by Salafist groups. Another factor that made this scenario difficult to achieve was the lack of a preexisting organized revolutionary Arab movement in Syria that could develop organic connections with the Kurdish revolutionary movement before the revolution. Once the first bullet is shot, the emergencies of war make it very difficult to build new bridges. The aforementioned “Euphrates Volcano” was a good step in that direction. Perhaps it could have happened earlier, but the opposition was a mosaic of different groups and factions, which made it difficult to establish coordination with a formal organization like the Kurdish Liberation Movement. Now, we can criticize the Kurdish movement for not pushing more for this scenario, but we have to understand that the first major encounter between the YPG and the FSA was in the battle of Aleppo, during which Al-Nusra repeatedly bombed the Kurdish neighborhood of Sheikh Maqssod. These clashes made coordination with the opposition more difficult. But in a scenario with better coordination, Bashar al-Assad would have fallen.

In a third potential scenario in which things could have gone differently, Kobanê could have fallen to ISIS in 2014. In that case, the revolution would have been crushed, Erdoğan would be relieved, and the caliphate would have become stronger and stronger. Game over. This could have had significant geopolitical effects. There are no revolutionary opportunities in this scenario.

In another potential scenario, the one that Kurdish supporters were dreaming of, would have involved connecting the three cantons along the Turkish border that have considerable Kurdish populations. After the liberation of Kobanê, the YPJ/G started the campaign that liberated Serêkaniye and Tal Abyad, connecting the cantons of Kobanê and Cizire. The operations to connect with the last canton, Afrin, got underway from both directions. This was the scenario that Turkey feared most: a whole border under control of Kurdish revolutionary forces could had been a nightmare for Erdoğan’s regime. When Manbij was liberated on the Kobanê front and the Afrin front started to shift across Tal Rifat, Turkey launched operation “Euphrates Shield,” a desperate bid to block the establishing of a full corridor under Kurdish control along the border. The race for Al-Bab became a crazy situation of great importance. Cooperation between the Turkish State and the Islamic State played a decisive role, with ISIS withdrawing to let the Turkish army take over those territories. When Turkish soldiers reached the doors of al-Bab, the dream of connecting the cantons was over.

Finally, it is worth mentioning something about the creation of the SDF. The SDF was a military umbrella created, in part, to allow the International Coalition led by the US to support Kurdish forces without clashing with Turkey. Turkey was threatening the United States that they would leave NATO if the US supported YPJ/G, so the US came up with the umbrella of the SDF rather than supporting the YPJ/G directly. For the Kurdish Liberation Movement, this step was necessary to ensure the survival of Rojava, to fight ISIS without letting Turkey crush the revolution. At the same time, it created dependency on the global imperialist hegemony, with all the contradictions and problems that entails. If a strong international revolutionary movement had existed at that time, things could have gone very differently.

Today, we are where we are because of what happened before, and we have to learn from it. As internationalists, we can see how our role, even if widely publicized in some media, has been little more than symbolic. We are far from being able to mobilize anything like the 50,000 internationalists who fought in the Spanish Civil War, and most of us were not very experienced revolutionaries when we arrived here. But we have the opportunity to learn from the struggle in Syria and the duty to translate these experiences to other revolutionary movements. One clear lesson is that revolutionary movements require time and experience to be prepared to play a significant role in any conflict, because the only way we can do it is developing organization and becoming a mass movement connected with the society.

A training offered by TA to expand the medical capacities of fighters in the Syrian Democratic Forces, teaching basic medical aid such as tourniquets to Kurdish and Arab fighters.

—What different scenarios can you imagine for what might happen next in the region? How can actions or developments outside the region shape which of these scenarios will come to pass?

Garzan: It is difficult to imagine positive scenarios. There are a lot of outside factors that will affect how the situation develops, but I can think of three likely scenarios.

1) First, we could see a progressive de-escalation of the conflict and stabilization of the region. This would involve negotiations between the self-administration and the Syrian state with the mediation of Russia, achieving some sort of formal status of autonomy. This would probably lead to the opposition political party linked to the MSD (Meclîsa Sûrîya Demokratîk, the organ of the autonomous administration working on a Syrian-national level) running in the elections in Syria, pushing for some democratization and reforms to recognize Kurds and other minorities, and formalizing some degree of self-administration for NE Syria.

2) Alternatively, we might see the continuation of the Turkish invasion. This could happen if Turkey gets the green light to attack Kobanê and occupy the city that stopped ISIS, or perhaps some other border town like Dirbesiye or Derik. The self-administration can’t allow Turkey to occupy more territory, so this scenario would probably lead to an “all in” last resistance against the invasion. This would also lead to the reorganization of Daesh if the occupation forces reach the jails where captured ISIS fighters are held, deepening the destabilization of the region.

3) In a third scenario, the one most wished for by revolutionaries, Erdoğan’s regime collapses. It is possible that fighting on too many open fronts could produce a crisis in the Turkish state. Ideally, the Rojava Revolution could become the blueprint for revolutions in Turkey and around the Middle East, opening the possibility of a wider revolutionary movement.

The various conflicts and power dynamics in the Middle East could open or close opportunities for the self-administration of NE Syria to cooperate with different actors in the region. The states that have significant Kurdish populations—Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, but also Lebanon and Armenia—will influence these developments, as well as the geopolitical powers that have leverage in Syria—Russia and the US. The next presidential election in the US could mark a change for their external agenda; it is not a secret that Trump and Erdoğan have not only personal relations but also business interests. Of course, public opinion can also play an influential role. The resistance of the Kurdish people has gained media attention and sympathy around the world.

Şahîn: Many of the aforementioned factors are things we have no control over. Therefore, it is very important to think about how we would position ourselves in different scenarios and what this means for today’s organizing, networking, and preparation. Looking ahead can help us to determine our steps today in order to make good decisions about the things we can control.

It is essential to see beyond the possibilities of this region and act internationally. No place in the world that dares to challenge the foundation of the nation-state, capitalism, and patriarchy can succeed in isolation. The struggle of the people of Rojava is something we need to translate to different contexts. Not copy-paste, but translate. Our Şehîd—our comrades who fell—are a big inspiration for us and when we speak about this topic, the words of ş. Helîn Qaraçox (Anna Campbell) really resonate:

“If we want to be victorious, we have to admit that our fight today is a fight for all or nothing, it is the time of bravery and decision, the time of coordination and organization, it is the time of action.”

We wish to see more people who say that they support Rojava or the YPJ, for example, to learn what this means in depth, to look around and seek their own Kobanês. Not in a literal sense, but regarding the values we build collectively and the need to defend them. We can find similar challenges in many aspects of our lives. We only need the will to change (incidentally, the name of one of our favorite books). Rojava cannot survive alone, despite all the support it gets. A strong revolutionary commitment must develop alongside it on a global level.

—How has the anarchist presence in Syria changed over the years, from its early beginnings to the IRPGF and TA? What developments or pressures have caused these changes?

Garzan: Anarchists came to Rojava inspired by the ideas of the revolutionary movement, the spirit of internationalist solidarity, and the will to contribute to the creation of a stateless society. In the beginning, every international was integrated in YPJ/G, but over time, some autonomous groups were formed. The IRPGF was the first anarchist group to publicly announce their presence in Rojava. They were focused on the military effort, the fight against ISIS, and also on producing propaganda materials to let the world know that anarchists are fighting in Rojava. That was an important step to give visibility to anarchists taking part in the revolution. Yet the IRPGF was unable to develop a solid structure that could sustain it, and after a year of activity and another year of inactivity, it was officially dissolved.

Tekoşîna Anarşîst was born with the intention to learn about the revolution with an anarchist perspective and to translate these experiences to our movements not only on the military level but also on the ideological, political, and social levels.

The interaction with other revolutionary groups in Rojava forced us to reflect more thoughtfully on what it means to be a revolutionary organization, how we understand what commitment is, how we conceptualize strategy and long-term aims…

Şahîn: Many anarchists arriving here already have critiques of the identity-based, liberal, or subculture-based character of some anarchism in the West. However, when you are here, these criticisms play out every day on a personal level. It is a very different culture and there are many people and structures with a long memory of struggle. So our rather small group is not extraordinary here. We are forced to be more conservative in how we carry ourselves, to learn the local social and revolutionary codes and conventions, including local languages, and to build relationships based on trust rather than lifestyle. This is not always easy, but it is worthwhile. It does not matter what’s written on your T-shirt (as we do not walk around in T-shirts and people can’t speak English), but how you act on your values in everyday life. This brings a depth and sincerity we sought but often couldn’t find in the places we come from. Every challenge brings reflections and new perspectives, and we go through changes here in many ways. One of the roles of the organization is to offer a common platform for these reflections and experiences so the lesson one person learns can become a lesson for all, in order that we can develop together in a more collective fashion.

The same goes for our approach to knowledge, skills, and analyses. Our members who work with the women’s movement don’t do this to become specialists for themselves; rather, they help to facilitate everyone’s development, just like the comrades who have new experiences or advanced knowledge in the field of combat medicine. They need to make sure that the collective can catch up at least on a basic level. With ideology, philosophy, and other perspectives in general we try to make sure everyone has access. With practical projects, people in working groups inevitably become more specialized, yet we should still be inclusive to new comrades and open to offering education.

We consider it important to have an organization that interacts with the locals and other groups on an everyday basis—some members leave for months to work in different places—yet still serves as a basis to establish our perspectives and future objectives together. Also, we should mention that many anarchists come to NE Syria without joining TA, joining other structures. TA does not represent all anarchists and other revolutionary internationalists in the region.

Ceren: Throughout the Rojava revolution, one thing that hasn’t changed is that the majority of anarchist women and non-men who come to Rojava do not choose to join our specifically anarchist structure, but instead join the YPJ, the women’s movement, or some other part of the movement here. Many comrades have seen the approaches of the women’s movement as highly compatible with their anarchist politics. I think this is something often missed by anarchists in the places we come from—that there are anarchists here, especially women, whose anarchist politics lead them to organize differently than we do. TA is an anarchist structure in Rojava, but it does not represent the entire anarchist presence in Rojava. Anarchist tendencies and comrades are present in the movement itself. Many of the biggest changes we have seen have taken place inside ourselves. Our collective has struggled a lot to develop a deeper understanding of our own politics and also of the ideas and practices of the movement here, and we have become closer to the movement here on some points, although we still have differences. I think the movement is coming to understand us more, too.

—Reflect on your experiences with TA as an experiment in anarchist intervention and solidarity.

Şahîn: I guess the way that we came here and act here is an experiment in anarchist intervention and solidarity. Our comments above should clarify the difference between charity and the solidarity we try to live here. Within that solidarity, there is also space for critical points of view and the space to progress after some failures. Perhaps a tangible example is the approach to non-binary, queer, and trans comrades. We find it essential that trans and non-binary friends can come and join the struggle here; at the same time, it is crucial to understand how sensitive the issue is here. Based on the lessons from the past, we seek to be supportive and create an inclusive environment while navigating the particular conditions of this region, which can be very tricky sometimes and hasn’t always been approached in the most reasonable way by some internationalists.

Botan: We remain militant in our commitment to show up as our true selves with pride, but we have learned from the mistakes of the past that the best way to do that here is to build relationships. It is also important not to imagine that western LGBTQ folks are the only ones engaging with these issues seriously and in good faith. Jineolojî and other structures concerned with women’s liberation also take up issues of gender beyond what we may think of as strictly for women. These issues are far from settled here. With this aspect of our revolutionary task, as with others, we have learned that connection with our comrades, even those who disagree with us, is important. These ideas don’t exist unless they exist for us in our daily lives.

There are many queer internationalists here, some nonbinary people, and even some people who have undergone or are undergoing medical transition. It’s difficult but not impossible to exist in this way as an internationalist here. A visibly trans person who comes here must consider continuing to exist and being in society as part of their militancy. We have seen from the experience of some TA members that sometimes locals who have a bad view of trans or queer people are still willing to work with us as comrades and over time to change their views as they get to know us as people and see our commitment to our common task.

Şahîn: Another particular example of anarchist intervention and solidarity could be the analysis of the need for combat medicine. We saw that within the people’s struggle from which we learn every day, there is a little gap we can help to fill up. We elaborated on this in a previous interview:

“Our teams were definitely not the first ones nor the only ones working as combat medics in North East Syria, but especially in the beginning it was rather rare. When we look back we see that there were three objectives within this work. First, to be able to do this work, to learn and be ready whenever is needed, to gain trust through our work and provide aid to injured comrades as quickly as possible. Second, to cooperate with the local forces in a way that would show through practice that this is very important work, pushing to develop this role within the ranks of SDF. And third, to see how we can share knowledge and skills with some interested comrades to multiply those doing this work, organizing education for other groups to provide more aid at the frontlines. We saw that it’s not enough to be a group of combat medics, and that every person should be able to help their comrades if they are injured and also to treat themselves. We have been training ourselves and comrades from other internationalist revolutionary structures, and just recently for the first time we have given a first responder education to SDF forces, which was a very important step as well as an enjoyable experience. Here everyone is a student and a teacher at the same time; what we learn, we pass on to each other.”

—As anarchists, how would you describe the goals that first brought you to Rojava? How do you measure the extent to which you have achieved those goals, or not achieved them? Have you noticed any sort of mission creep in the time you have been there?

Garzan: TA is composed of anarchists from different parts of the world and with different backgrounds, but the main goal has always been to support this revolution and learn from it, and to become more capable of organizing revolutionary movements in our own places. This support and learning belongs to short-term goals and it is something happening day to day, and we can say we are offering our grain of sand to contribute to this revolution. The more long-term aims will need to be evaluated as time goes by. Right now, we are a more consolidated structure in Rojava. It is known here and outside that anarchists are part of this revolution together with other revolutionary movements and organizations. But the ideas that inspired this revolution go far beyond Rojava, bringing together all these different revolutionary movements to make a common front against capitalist modernity.

With all this, the original idea of coming, learning, and going back stayed the same for some of us. For others, the friends we met here, the connection with this society, with the revolutionary project, led to making a more long-term commitment to this land and these peoples. A place like this, an autonomous territory where revolutionaries from all around the world can meet and discuss freely, offers an opportunity to put in practice the idea of building a revolutionary society—with all the contradictions that entails—a place to learn and develop together the society we had been dreaming about.

Botan: Many internationals come here to learn what a revolution looks like in real life. Many of us feel it’s important to bring and lift up anarchist principles that we see this revolution has space for and can benefit from. Many people come here because they cannot watch the genocide against Kurds, Armenians, and others happen from afar. And of course, the women’s role in the revolution and the focus on social ecology are widely respected and draw participants from the West.

Şahîn: With the collective growing, in other words with all the mistakes we have made over past three years, and reflecting on them, some sort of change of goals has been taking place. This comes with the experiences we have had and the capacity and trust we have built—and the possibilities these make it possible to imagine. There are moments in our past that we are not so proud of, as well as achievements that we couldn’t have imagined two or three years ago.

As some of our goals take a more concrete shape, they bring shorter-term challenges. For example, as anarchists, one of our goals is gender liberation, so women’s liberation here is one of the topics we came to draw inspiration from. It is one thing to say this; to put it into practice is another thing entirely. That is the challenge we face now—to have the non-male part of the organization even stronger in numbers in order to balance (or outnumber) the male one, and to make sure that the “xweser” (autonomous) women and non-male part becomes in a way the driving force of the organization. We do not talk about identity-based separatism, like in the West; rather, we see the integrity and solidarity of women and non-men as a counterweight to the inertia of thousands of years of toxic masculinity that affects every aspect of our lives and the ways we see ourselves and others. To surprise of many, this may be one of the best places in the world to figure this out. Not in a closed anarchist bubble, but on the contrary, in everyday life and organizing with people around here.

This relates to many of our discussions. As anarchists, we are against the state, capitalism, patriarchy, etc. But we are more interested in discussing what we are for, how to get there, how to defend it, what people’s self-defense entails in a deeper and broader sense. With time and experience, both positive and negative, we aim to distill common perspectives and direction. That means to make a roadmap backwards—aiming at the destinations far away, the utopia, trying to see where we converge (as well as learn from where we diverge) and draw on the experiences we have from our backgrounds mixed with the lessons from our lives here to create common analyses in order to figure out together what nearer milestones we need to aim towards. That helps us to figure out how to focus and choose particular strategies and tactics. Not necessarily a blueprint, but with time we came to the conclusion that having some formality and common principles to the way we organize can help us to name and work against “invisible” informal hierarchies and stagnation. I guess that’s quite a “mission creep” from the goals many of us arrived with.

—To what extent have your efforts helped to foster horizontality and autonomy throughout society in Rojava?

Garzan: First, we have to highlight that we are a small and young organization compared with the size and history of the Kurdish liberation movement, and we have to be humble regarding our capacity and influence on what’s happening around us. Furthermore, our focus as a military organization kept us away from civil society at the beginning, and armed forces are not the best place for horizontality. With time, we got more connected with civil society, meeting families, neighbors, and local organizations, especially once we learned Kurmanci.

We understand autonomy as self-management, as the capacity to address different needs and problems without creating dependency on external factors. In the medical field, we work to support hospitals and medical infrastructure, and we get to know the doctors, nurses, drivers, cooks. Now we are working on education sharing what we have learned over the past years here, and also on a project to mass-produce DIY tourniquets in coordination with the health committee. We have also learned that very few people know about anarchism, only the more politicized ones who are curious about other political movements. But horizontality and autonomy are not exclusive to anarchism. Many friends we have met here are committed to these values.

A few years in, we are learning a better idea of how civil society works here. The patriarchal dynamics and family-clan structures are very present, and hierarchical dynamics are often interconnected with a feeling of respect and belonging to the community. At the same time, the war, the revolution, and the liberation struggle made everyone think about politics and society. For the Kurds, the opportunity to express their own identity, to say openly that they are Kurds, to learn their language in school, made them more aware of the oppression they were experiencing. For other minorities, similar stories can be told, even if some just feel that Arab hegemony has now been replaced with Kurdish hegemony without bigger changes.

With Arabs, this is a very big topic, because there are a lot of different clans and groups among the Arabic population and most of them also suffered severe repression from the Ba’ath regime. The ones that are actively taking part in the efforts and structures of the self-administration are bringing a lot of motivation and hope for a self-organized future that they did not imagine before. And for them to see internationals like us is always a source of fun and curiosity. They ask us why we came here, why we are not going back to our homes, if Syria is nicer than our countries. When we talk about politics, they often listen, as if we are telling them stories from other places. Sometimes I wonder whether they listen to us because they are interested or just because we look exotic. But with those with whom we get to develop more long-term relations, they get to know us and trust us, and we can build friendships and connections.

Ceren: To be honest, I don’t see that our efforts have either helped or hurt the fostering of horizontality and autonomy throughout society here. But I can see how the society here has deepened our understanding of these things. These are not new ideas here by any means. The principles of autonomy and self-determination are built into Democratic Confederalism, which is developed in practice every day by the people who have become involved in the self-administration of their communities at many different levels, and we learn a lot from the methods the movement is using to engage people in this process and from the problems and mistakes that arise as well. We have found that the practices we have learned from the movement here, such as tekmil [a form of collective criticism], have been helpful in breaking down informal hierarchies to some extent and mitigating some of the potentially coercive elements of hierarchy in times when it is necessary, so that this hierarchy does not extend further than is needed.

—What factors have you seen contribute to hierarchical structures consolidating control in Rojava? Which elements of society have been most resilient in maintaining or defending genuine horizontality?

Mahir: Some parts of the society here also have a very feudal-patriarchal mentality; this means that the society is based on strict hierarchies and dogmatism. The man is the oppressor in the family, while the wife and the kids are under him and they are focusing on “satisfying” his wishes. In the tribes, there is also a hierarchical structure… Here, people have lived under state oppression all their lives. They faced a lot of repression in order to create different ways to organize. They were not allowed to come together and open small companies, buy land or even cultivate it, or build their own houses. They were only permitted to harvest wheat and sell it to the state. So this means that the different peoples and minorities were prevented from organizing cooperatively, which is the essence of all societies. This is creating some problems in terms of self-organization and working together.

On the other side, against these hierarchies, we have the forefront of this revolution, the women. They are tired of hierarchies and patriarcal domination. They are the ones with more energy to continue the revolution and to push forward, but they are not alone. The workers and peasants are struggling to create more cooperatives and develop the ones that are already existing, to be able to make decisions themselves about the crops and what to do with them. The economic committee is creating a lot of cooperatives for vegetables, anti-corona masks, and pharmaceuticals. The hevserok system (a co-president/co-chair system necessitating that at least one man and one woman represent any organization) is working in every structure of the autonomous administration. There is a lot of effort to avoid constructing a monopoly of power, with a bottom-up system, creating different forces for various ethnic groups, such as Sutoro [the Assyrian and Syriac Christian community security forces] or HPC [civilian neighborhood self-defense units organized on a local municipal level in coordination with YPG and YPJ].

Here it’s good to mention the method of tekmil: critique and self-critique based on a horizontal approach coming from the philosophy of “hevaltî.” A revolutionary approach to camaraderie, a way of striving not only to develop oneself but always to support comrades in their development, to believe that everyone has the capacity to change. You give value to every critique that you receive from any heval (comrade) and you are responsible for criticizing every comrade according to the same principles and the same values. You don’t give more or less critique to someone based on whether you like or dislike them. Irrespective of responsibilities or your position, in the tekmil, everyone is the same—we share the same values and aims and use criticism and self-criticism to go forward.

Şahîn: The main factor is always friendship and trust among comrades, ensuring a healthy environment where critique and self criticism can be presented if hierarchical dynamics develop. In one word, hevaltî. To be able to support our heval, we need empathy, to listen to each other’s perspectives and understand others’ feelings, to be willing to learn and find solutions instead of obstacles. To be able to find these solutions, we also need curiosity about what we are doing; we must move away from seeing political organizing as a suffering we have to endure until we have freedom. We should strive to create the life we want to live now. We need to be committed not only in a sense of self discipline, but committed to our comrades and to what we are fighting for, to take on responsibility and maintain organizational integrity. To think and act in a collective way also means to be conscious about the dynamics in the group or organization and not shy away from contradictions that will inevitably open up, and in these moments, to give value to our comrades and their work, and maintain morale especially in the times that it is hardest to do so. How we relate to others can change our possibilities moving forward.

—Today, in the United States, there is a lot of talk about impending civil war. What can people around the world learn from the Syrian experience of civil war?

Botan: There has been talk of possible civil war for the past few years in the US and it seems to be reaching a fever pitch. I think it’s unrealistic to expect a struggle for land the way you see in Syria—people in the US generally don’t have the same connection to the land and the fascists in power already have control over all the territory. It’s more likely that if armed resistance from below occurs in the US, it will be something more like the Irish Republican Army in the cities of Ireland in the past century, in terms of the majority of the population. However, the communities with the strongest ties to the land in the US and with strong identity and networks are those of Native American communities. They have histories of resistance and the revolutionary potential to lead a true transformation of society in so-called North America.

Şahîn: One of the key lessons is not to make enemies needlessly. Seek points of convergence, not conflict, when meeting and organizing with people. I believe it is a mistake to base your politics on sharing the same enemy or hatred. Be aware of what the essence of your political aim is. Not solely from a strategic point of view but also, for lack of a better word, from a philosophical one. In the end, everything comes down to the question “how to live life,” and if we share this with everyone we live and organize with and learn from, we need to have something with more substance than “We are here together because we hate Erdoğan, Trump, Nazis, patriarchy, racism…” Seeking the things that connect us with the people we share our lives with, outside of empty concepts like “American” or “white,” and living this deeper meaning and joy of life (and struggle) every day can enable people to realize that the things they hated others for are not important.

Again and again, history shows us that we may never have all the cards in hand to prevent a civil war. But we should not romanticize it; we should act to minimize its impact and the strength and size of the forces we may have to fight against. It’s good to be ready, but do not underestimate the importance of social organizing as well as building underground networks—and definitely do not romanticize war.

Ceren: War is the ultimate expression of patriarchy. It is a game in which the primary method of moving pieces is coercion. Sometimes the enemy creates such a reality that it is necessary to enter into war, but it is not something we love or see as a goal, it is something that sometimes occurs on the path towards achieving our goal of building free life. We are not afraid, ashamed, hesitant, or uncertain about the necessity of self-defense. Our hatred of war does not make us less ready or willing to fight for freedom and life; in fact, it sharpens our understanding of what we are doing. Our clarity and our love of life and freedom distinguish us from our enemy; they are something sacred and a source of strength. Abdullah Öcalan observed that every living creature has a mechanism of self-defense, and comrades in the mountains live close to nature and take care to learn from all the life around them. A lot of knowledge about self-defense has come from plants and animals. What we are taking part in is self-defense, which is an expansive concept that is part of the very fabric of society.

A civil war is necessarily a mess, and it is not necessarily a revolution. A civil war is something that we fight in order to defend the revolution, but winning a war does not liberate a society from colonization, patriarchy, and capitalism. That work is a constant struggle within ourselves and within society, and it’s an all-hands-on-deck situation. Honestly, I worry about the way that revolution is often understood where I come from—as a thing that is glorious, violent, and singular. A revolution is a process of healing, something that is made much more difficult by constant attack. In times when there is a ceasefire, the advances we make in the revolution are massive, and in times of great threat and violence, we experience the most setbacks and find ourselves compromising some pretty important things. I would recommend that comrades get as excited about building up things that are worth defending as they are about the aesthetics of armed struggle. The truth is that war can wear people down, and when it goes on long enough, people get increasingly tired and will accept things that they wouldn’t have accepted before in hopes that the war will end. There are people here who think about leaving simply because they want their children to live without war for some part of their childhood. It takes strong social connection and a deep ethical foundation for a society to face the enemy and refuse to accept domination. This is what we have been learning about civil war.

As far as what is realistic—we will build free life. How we are going to get there is something we are all figuring out together every day. It is unrealistic to select methods and approaches that are not formulated in relation to the ultimate aim of building free life, then expect those methods and approaches to advance the struggle for free life. If we want victory, we have to be led by our aim, not by our impulses or by what is familiar yet hasn’t worked. This is also something we are learning from the movement here. We have to be open to trying new things, to making mistakes and learning from them. Beyond that, I don’t concern myself with what is realistic or unrealistic, because our ability to understand those things has been altered by our socialization in a system that wants to destroy our ability to imagine and believe in possibilities outside of it.

I think all revolutionaries have to be a little crazy in this way—we believe in the impossible, so we change what is possible.

—In the past several years of struggle, what have you learned about what it is possible to accomplish with weapons, and what weapons cannot accomplish? What are the advantages and drawbacks of organizing armed groups that have a distinct role apart from other aspects of social life and struggle?

Şahîn: This comes again to the question of the examples and lessons we take from the YPG, the YPJ, and the Rojava revolution. It’s easy to think of liberation as something that takes place only in heroic moments on the battlefield. Those are important to remember, but there is much more to it. One of the most important aspects of the struggle that people tend to pay little attention to is the social fabric that provides the foundation for the defense of any uprising or liberating struggle. If we focus solely on training for armed conflict, if we analyze victories only according to a military perspective, we will not reach deeper changes.

For every fighter in the YPG and YPJ, there is a family ready to open a door, share a roof, to offer blankets, food, everything they have. For every military training, there is also ideological education. Not only in the military academies, but also in society at large and in autonomous women’s spaces. This hasn’t come overnight and it is not a coincidence. There is so much we need to include in our thinking when we speak about freedom and community self-defense. Some of these things are in contradiction with each other, which is even more of a reason to make sure we seek tools to prevent toxic masculinity when practicing tactical skills.

Success demands complete and long-term commitment to redefining culture, which will not be achieved in a single training. Many experienced (or wannabe) soldiers from outside Syria have come here and complained about the “bad military organization” of the SDF. Well, no one thinks there is nothing to improve and from a technical point of view, some of these critiques may be right. But still, they are not constructive, because they show no will to go deeper in understanding what liberation here is actually based on. They come from a typical colonial white “know-it-all / savior / mansplaining” mentality.

We would advise anyone to go deeper into what the Rojava revolution and the self-defense paradigm is based on, especially for comrades interested in or practicing armed and tactical training or self-defense.

Botan: It’s important for anyone trying to understand the role of weapons to understand how drones have fundamentally changed the nature of the war here. Basing one’s understanding of the tactical situation here on the images from the time of the conflict in Raqqa, for example, gives the impression that the fight is primarily waged with small arms. In fact, up until the American withdrawal, a large factor in our favor was air cover. With the shift from Americans as allies and Daesh as the main aggressor to Turkey as the biggest threat, the nature of physical battle here has also changed immensely. This makes strategy, cohesion, and all the things mentioned in the previous paragraphs all the more important. There is less and less of a place for the icon of the tough guy with a Kalashnikov who wants to “fight evil” in a straightforward camera-ready way—an image that was always an oversimplification.

Ceren: A weapon cannot teach you how to love. It is easier to teach a revolutionary how to shoot than it is for a man who loves guns, war, and fighting to learn how to make a revolution, regardless of whether he is a great shot. Any day of the week I would prefer to be at the front with a revolutionary who has never shot a gun but understands with total clarity why we struggle and what we are defending, than with the most militarily capable person with no ideology. Weapons and all the military training in the world do not make people ready to do what is needed, not when we are defending a revolution. Maybe in an imperialist military, weapons and military training are enough, but we are not an imperialist military and we don’t have the resources they have—we have hevaltî. Weapons don’t build a revolution. Although they are certainly useful in helping to defend a revolution, they are only one part of the defense. Without every part of the system of self-defense working together, Rojava would not exist.

One interesting thing about a rifle is that it can provide a bit of an equalizing effect. Most women can be physically overpowered by at least one man in our lives. But a woman or non-man with an AK-47 and the knowledge and confidence to use it, in a system that supports her in developing self-determination—well, that changes things. It’s not enough, but it’s something.

As far as the drawbacks of organizing armed groups… one drawback is the people who tend to show up. Armed groups generally attract different kinds of people than other kinds of groups. Men are socialized to have a relationship with violence that is ultimately destructive. They need to overturn this in themselves. Even many anarchist men have not done this work before they show up to an armed group. Many women and non-male comrades are pushed out of these groups by patriarchal dynamics, or don’t show up in the first place because so many other projects would fall apart without the invisible work they do that men often don’t take up because it isn’t sexy or glorious work, or because they have been unable to access a process of learning how to use weapons that actually helps them advance rather than tearing them down. Autonomous structures are essential for all these reasons. It is also important for men to take a serious look at the foundation of their politics. Armed leftist groups cannot simply be a more “woke” version of LARPing, or a way to do all the same things right-wing militia members do but with a different aesthetic veneer. Armed aspects of self-defense must never be separated from other parts of revolutionary struggle.

Political education and practice, a love of freedom and life, and a deep respect for women’s freedom is essential for absolutely every armed militant. Otherwise, what are we doing here?

Diyar: It is also important to contrast the connection that fighters in Rojava have with the local society, so much so that the two can seem inseparable, with the situation in the “US” and in much of the West. Many anarchist spaces in the “US” are primarily white and middle-class, often situating them outside of the Black and Indigenous communities from whom resistance to the American state springs organically and historically. In practice, many anarchist “self-defense” projects do not defend anything beyond their subculture. This leads to a rise of specialized projects, rather than an actual means of “community defense.” This doesn’t just manifest in racialized dynamics—the development of specialized groups also serves to isolate other anarchists and members of that community. Rather than becoming skilled in the tactic of self-defense, or making that a common skill in our circles, many who get involved in this tactic “join” an armed organization, or make that their primary or singular mode of political involvement.

The concentration in the “US” on building a “leftist gun culture” has not resulted in a culture of self-defense, but yet another branch of political activism, often dominated by men. To overcome this, it is important to understand what, exactly, we are defending. What community do we belong to? Until we answer that question in theory and practice, we can’t make any meaningful progress. We must not wait for the crisis to deepen to resolve these contradictions. This is not meant to say “do not train, do not prepare” until this is resolved, but we should always seek to make resolving this contradiction something that happens because of our methods of training and preparation, not in spite of it.

—Finally, do you have any guidance for people who have lived through traumatic events in the course of armed conflict and are attempting to reintegrate into their communities? What have you learned from people who have organized or fought in Rojava and then returned home?

Botan: It’s important for friends returning to stay in connection with comrades and check up on each other. There have been suicides among people returning to the West, not only because of the impact of traumatic events but also because of withdrawal from the way of life experienced here. Capitalist modernity is cruel and isolating. Connection to other people and having the space to open questions about mental health without shame are key factors in dealing with these issues. There is a myth that war is like a gold standard to measure other types of trauma. This can create a hierarchy of suffering.

Ceren: Something we have learned from friends in the women’s movement is that healthy life is free life, and that we must take initiative in our visions of free life. We often find ourselves in situations in which we must react, must give a response. Despite this, a responsibility we cannot neglect is to proactively develop ways of life that are not a reaction to the present system or circumstances, but rather are built on foundations outside the hegemonic system. We need a deeper understanding of what we are are trying to describe when we use words like trauma. We need communities that are compatible with revolutionary life. Frankly, individualism and other forms of liberalism are alienating to comrades who come back from Rojava because of what they have learned living with comrades here. Our communities need to integrate into the revolutionary freedom struggle. What is needed is not for the comrade returning home to reintegrate into a community that is like the one they were a part of before they came to Rojava; what is needed is a meeting of this community and the comrade as they are now and a mutual development.

We cannot change ourselves without changing the social systems we are a part of. No individual solution will solve problems as deep as the ones we are facing. It is always most sustainable and most revolutionary to build collective solutions, and dealing with heavy events is no exception. Here, we have seen that it is possible for us to live through things that would have been unimaginable to us in other contexts because of the way we live together. In order to face the most difficult things, we need strength and resilience, and we are strongest and most resilient when we are connected to others and share a collective life based on a love for each other and for the freedom struggle. Entire books could be written about hevalti, or comradeship, without even scratching the surface of what it means to look at your comrades in the toughest moments and know that you will struggle together and believe in each other until the very end. We face everything together—so things can be a bit messy sometimes, but heavy things become lighter when we carry them together.

There is also this concept of “giving meaning.” When friends fall şehîd, it is a heavy thing to feel their loss, but the meaning we give to their sacrifice and to what they struggled for drives us forward and gives us strength. We can never feel helpless or allow ourselves to become objects that things happen to—when we grasp our agency, when we see ourselves as revolutionary subjects, we are empowered to change things and so we can live in our faith. Depending on what meaning you give, every person you know who falls şehîd can be a foundation-shaking personal loss that destroys one’s ability to struggle and connect to life, or can be another reason to fight for freedom. When we think of our fallen friends, we are reminded of the sacredness of every moment with comrades, and then maybe we can notice a bit more the people around us, and see our own role in their lives and our responsibilities to them and to the şehîd.

We honor our comrades by taking up their struggle. Joy and pain exist in every moment, hope and despair, presence and absence—which of these do we sensitize ourselves to? What do we honor and make room for? The approach we take also affects our comrades, because our joy and pain is shared. If we feel our pain most, our comrades feel it, too, and it is reflected and multiplied and becomes much heavier. If we panic, it can spread in ripples to everyone we come into contact with. If we feel our joy most, the morale among comrades multiplies and we all become stronger.